When he was alive, Ficre Ghebreyesus was chiefly known as the chef and co-owner of the Caffe Adulis in New Haven, a restaurant inspired by the cooking of Eritrea, his homeland in East Africa.

But he was also an almost secret painter. Now, 10 years after his death and just two years after his debut New York exhibit, Ghebreyesus the painter has ascended to the art world’s most celebrated stage: the Venice Biennale.

He has five paintings in the show running through Sept. 25. The biggest, “City with a River Running Through,” is almost 20 feet wide. Described in the Biennale catalog as “a patchwork of orange and peach colors,” it looks abstract, but in fact borrows patterns from Eritrean basketry and embroidery.

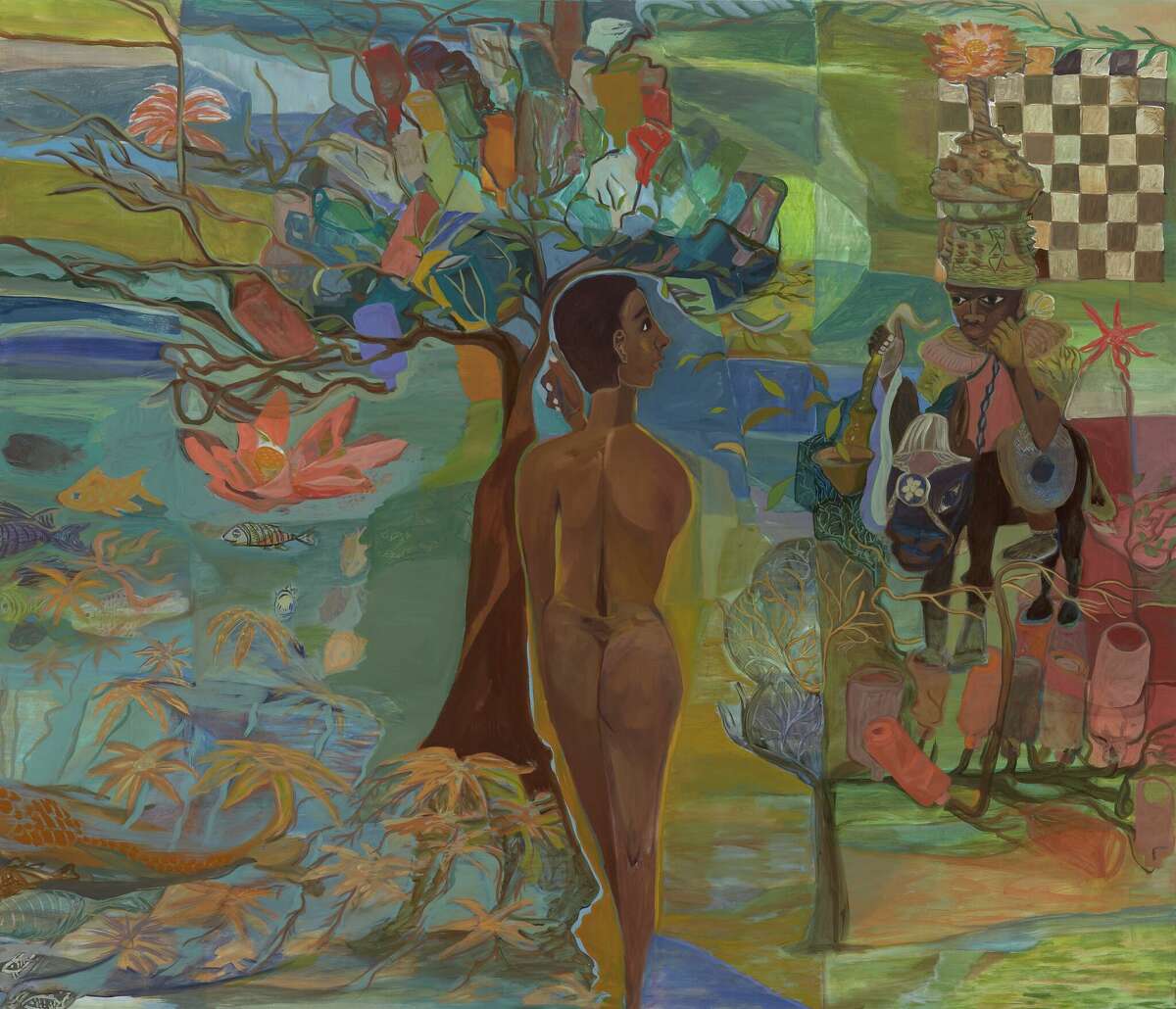

Ficre Ghebreyesus’s “Nude with Bottle Tree,” c.2011.

Acrylic on canvas 72 x 84 in (182.9 x 213.4 cm). The piece is on display at the Venice Biennale.

Another painting, “Nude with Bottle Tree,” is small by comparison, only six feet high and seven feet wide, but it is more figurative. A naked person, perhaps the artist himself, is seen from behind, his gaze distracted by a strange figure, combination warrior and jester, mounted on an ornamented donkey. The rider and donkey are figures from West African folklore.

Both paintings are dated 2011, the year before his sudden death from a heart attack at age 50. At the time he was married to Elizabeth Alexander, a Yale professor, writer and poet, who would later write an acclaimed memoir, “The Light of the World,” dedicated to him.

The most iconic artist discovered after death is, of course, Vincent van Gogh, but Ghebreyesus was different. He didn’t suffer from lack of recognition as van Gogh did. He avoided it. Even though he took painting seriously, getting an MFA from the Yale School of Art in 2002, he almost never showed his paintings during his lifetime. Yet he amassed more than 800, many influenced by his youth in Eritrea, then engaged in a long war of independence from Ethiopia.

His first local posthumous exhibit was at the Artspace in New Haven in 2013. The wider world would come to know Ghebreyesus as an artist in 2015 when Alexander published “The Light of the World.”

Elizabeth Alexander and Ficre Ghebreyesus.

Courtesy of Elizabeth AlexanderHowever the book read then, it now has passages of new, piercing poignancy. Alexander wrote about when she and Ghebreyesus met in 1996, “the first thing he wanted to do was show me his art.” Later, she writes that Ghebreyesus was shy about his artwork, only willing to show it in his studio, despite the urging of many champions to exhibit.

“People will know this work after I’m gone, sweetie,” she wrote he would say to her. “He said it with a laugh, but he meant it.”

Ghebreyesus became a refugee at age16, passing through several countries before arriving in New Haven and opening Caffe Adulis with two brothers. In an artist’s statement submitted with his art school application, he wrote of the saints and angels he saw in Eritrea’s Coptic churches, of its ancient crafts and cave drawings as well as the “vision of hell incarnate” from its war with Ethiopia. In the closing paragraph, listing his dreams for the future, he wrote: “For one, I want to be a very good painter.”

Ficre Ghebreyesus’s “Fish,” c.2008-11. Acrylic on canvas 72 x 84 inches (182.9 x 213.4 cm).

© The Estate of Ficre Ghebreyesus Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New YorkGhebreyesus got his New York debut in a pair of 2020 exhibits organized by Galerie Lelong & Co., which had come to represent his artistic estate. (Another artist on its star-studded roster is Yoko Ono.) The gallery coordinated the loan all five of his paintings in the Biennale from private lenders and the artist’s estate.

Lindsay Danckwerth, the gallery’s director of special projects who worked on the exhibits, said Ghebreyesus’ enormous “City” painting borrows from quilt-like maps he made before applying to art school .

“Time does not feel linear,” Danckwerth said, describing his work. “It feels like he’s pulling from memory, from dreams. He’s pulling from lived experience. It’s almost as if time is suspended.”

Coincidentally, the theme of the Biennale is “The Milk of Dreams,” borrowed from a book by the early Surrealist painter Leonora Carrington. Works by women and surrealism dominate the central exhibition of more than 200 individual artists. In an overview essay, the Biennale’s chief curator wrote that “the rediscovery of art’s myth-making potential can be seen” in Ghebreyesus’ large-scale paintings.

Danckwerth was among the local contingent that went to Venice for the official opening April 23. She said Alexander and her two sons with Ghebreyesus also made the trip.

At the time, Alexander, who is now also president of the Mellon Foundation, was in the midst of a promotional tour for her latest book, “The Trayvon Generation.” In “The Light of the World,” she tells how her husband had waited up for her the night before he died.

“He loved hearth above all else,” she wrote. “The best and worst of the world were all in his head. He put it on canvas and gave it to us.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated to clarify how long ago Ghebreyesus died and that his 2013 exhibition was held posthumously.

More Stories

What Are Examples of Gourmet Foods?

Penning Down The Names of Top 10 Celebrity Chefs in The World

Tips for Choosing Culinary Arts As a Career